Gess

Copyright (c) 1994 Puzzles and Games Ring of The Archimedeans

This game was invented by the Puzzles

and Games Ring of The Archimedeans in order to create a generalization

of Chess.

The game uses a 18x18 Go board (or a

typical Go board using the squares, not the intersections), with 43 white

and 43 black stones. The game starts with this initial setup.

-

PIECE - A piece is any 3x3

cells square containing at least one stone, at its referred by its

middle cell.

-

RING - A piece with 8 stones,

and with an empty central cell.

-

MOVE - The non-central stones

define the move directions, and the central stone define the range.

-

A piece may move on a certain

direction if the piece's cell on that direction (relative to the

middle cell) has a stone.

-

If there is a stone on the middle

cell, then the piece may move 1+ cells on any valid direction.

Otherwise, the piece may only move up to 3 cells on any valid

direction.

-

A piece may continue to move if

there are no stones on the 3x3 cells that it crosses.

-

CAPTURE - If a piece occupies

one or more enemy cells along its moving, they are captured and the

piece's move must stop.

-

GOAL - A player wins if he is

able to remove all opponent's rings.

Checking the initial setup, we see on each of

the last 3 rows: a Rook, a Bishop, a Queen, a King (the Ring), a Bishop and a

Rook. In the 6th and 13th rows, there are 6 black and 6 white Pawns.

|

|

Moving samples

The White piece centered at the stone on the left of cell [1] can move

any number of cells, to the bottom and to the bottom-right. Moving to

the bottom captures two Black stones, moving bottom-right captures one

Black stone.

The Black piece centered on the left

of cell [2] can move to the top and can capture two White stones. That

piece cannot move into the top-right direction, since there is a

friendly stone blocking its progression.

|

There is an article about Gess on

Eureka Magazine #53, which is the journal of the Archimedeans, the

mathematical society of the Cambridge University. More info at

BGG.A similar game, that uses group shapes to

move them together in 2017's

Troop Chess

by Ył dǐng jiě. From the

BGG description:

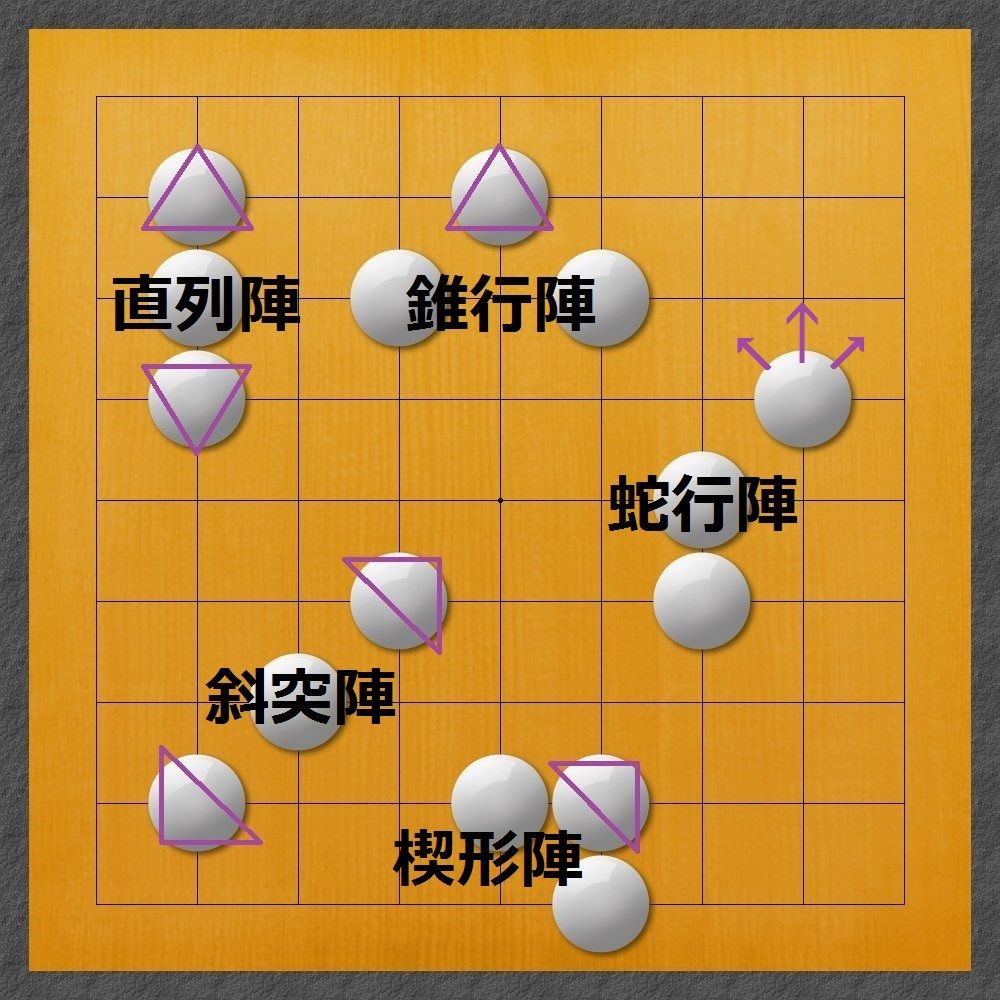

集団陣形棋 (Shudan-Jinkeiki) (Troop-Chess) is an

abstract game for two players, which can be played using components from

other games (such as Go, Chess, Shogi). In Troop-Chess, players organize

battle-formations with their pawns and use these formations in both offence

and defense.

The game can be played in three versions, each

using groups of three, five or eight pawns. A player can take action only if

they have organized a battle-formation using the specified number of pawns.

For this reason, a player who has reduced their

pawns to fewer than the specific number, or has divided them too small,

making it impossible to organize any formation, will lose the game. It is

possible that both players get incapacitated at the same time, because they

have reduced their pawns too much simultaneously. In this case, the game

ends in draw.

Each type of battle-formation has its own nature,

such as strong in attack or highly maneuverable. One formation has only

mobility. As well as the predefined formations, you can create original

battle-formations as you like. And modify the number of pawns that are used

too.

Each pawn does not have any nature by itself, but

the power or strength of the formation organized from pawns is affected by

its relationship with the neighboring pieces.

What is required to determine this is only a method

to judge which are allies or enemies.

Further, whilst in the original game, each pawn has

no nature itself, the designer encourages players to customize the game

further by introducing specialized pawns.

Another game that

mixes Chess and Go, is

Go-Chess by Jim Callan.

Since the original links are dead, here's the info I was able to recollect from

the Wayback Machine (Jan

27, 2002):

Go-Chess Rules of Play

Object. The object of the game is to checkmate the opponent’s king.

Board and Pieces. The Go-Chess playing board is a 10 x 10 matrix of

squares, alternately colored light and dark. Ten randomly chosen squares on

the matrix are “blocked off” (colored black). Every board is different,

since a different set of ten squares is blocked off for each new game.

Unlike chess, there is no directionality to the board, i.e., no home side

for either player. Each player has a standard set of chess pieces, one white

and the other black. The pieces move and capture just as in chess, except

that pawns can move one rank or file at a time in any direction and can

capture an opposing piece that is one diagonal square away in any direction.

No piece can be moved onto a blocked off square. Queens, bishops and rooks

cannot pass over a blocked off square.

The Piece Placement Phase. There is no

predetermined initial position for any piece. Instead, the play phase of the

game is preceded by a piece placement phase, where the players select the

initial positions for all their pieces. To begin this phase, each player

selects an initial position for a pawn without revealing it to the opponent.

Any square that is not blocked off is eligible. After both players have made

their selections, the two pawns appear on the chosen squares simultaneously.

Then the two players place their second pawns in the same fashion, selecting

any available squares. The remaining pieces are then placed in the same way,

in the following order: all eight pawns, then the two bishops, then the two

rooks, then the two knights, then the queens, and finally the kings. Bishops

must be placed on squares of opposite colors.

If ever the two players choose the same square for the pieces they are

placing, they must select new positions for them but neither may choose that

square. If once again they make the same choice, they must select yet

another square and may not choose either of the two squares they previously

tried. This process continues until the two pieces have been placed on

different squares, with the stipulation that none of the squares previously

attempted for that piece are permitted. The slate of ineligible squares is

cleared for the next pair of pieces to be placed.

Kings may not be placed in check. If the kings are placed such that neither

is checked by a previously placed piece but they check each other, they must

be placed again and neither player may choose a position previously

attempted for his king. A player may select a square the opponent has

attempted for his king as long as the player himself has not attempted to

place his king there.

Determining the First Player. Unlike chess, white does not

automatically move first. Instead, the player whose king and queen are

closest together moves first. Distance between pieces is determined by

adding the number of ranks they are apart to the number of files they are

apart.

If the king-queen distances are equal, the player whose king is closest to

his nearest knight moves first. If that distance too is the same, distances

between kings and other knights determine the first player. If those

distances are again the same, the determinant is distance between kings and

nearest rooks, then kings and other rooks, then kings and nearest bishops,

then kings and other bishops, then kings and nearest pawns, then kings and

next nearest pawns, etc. If none of these criteria determines a first

player, white moves first.

The Play. Play commences and proceeds as in

chess, the players taking turns until one checkmates the other or a draw is

reached according to the standard rules of chess. There is no castling, no

pawn promotion, no initial two-square move option for pawns, and no en

passant capture. Stalemate is a draw, as in chess. If both players make

identical pairs of moves three times in a row, the game is a draw. A draw

can be declared at any time by mutual agreement, where either player offers

a draw and the other accepts.

Go-Chess Hints on Play

-

It pays to examine the board layout and begin

developing a strategy before placing even the first pawn, although

inevitably this strategy will have to be adjusted as your opponent

places pieces.

-

It is suggested that players begin by planning

possible locations for their kings and queens, bearing in mind that the

player whose king and queen are closest together plays first—a distinct

advantage. You might plan for the eventuality that the kings and queens

are equidistant by plotting locations for your knights that are close to

your king, since distance from kings to knights are the “tiebreaker”

when the kings and queens are equidistant. Seldom are second and third

level “tiebreakers” required, and so distance between kings and rooks,

bishops, and pawns should not play important roles in your strategy to

gain first move advantage. However, it often makes sense to pack a

number of pieces around your intended square for the king for defensive

purposes.

-

It may not be wise to count on being able to place

your king on a single square, since it is too easy for the opponent to

anticipate this strategy and foil it by placing a piece of his own on

this square or by checking it. It is better to plan a “pocket” of

several protected squares where the king might be placed, or even two

pockets.

-

One piece placement strategy is to be mostly

defensive, packing most of your pieces around the intended square for

the king. However, you might consider trying to anticipate your

opponent’s strategies and attempting to foil them by placing pieces of

your own amidst the opponent’s “camp,” as long as this does not entail

undue sacrifice to your own position. Since foiling a strategy often

comes at a price—placing a piece where it can be easily captured—the

merits of doing so should be carefully weighed. Placing your eighth pawn

in the middle of a pocket your opponent has developed might make sense,

whereas placing a more valuable piece there might not.

-

The relative value of pieces is not the same as in

chess, and in fact varies from board to board based on patterns of

blocked off squares. A board with many open ranks and files adds value

to rooks. If a preponderance of blocked off squares are of one color,

bishops on squares of the other color are very valuable. Knights are

very powerful since only they can cross blocked off squares, which might

be the best way — or even the only way — to attack a well-protected

king.

-

If you feel sure your opponent is about to select

a certain square for the next piece to be placed, consider selecting the

same square. If indeed you both choose that square, he will have to make

another choice. The effect is to foil his plan at no sacrifice to your

own. The danger, however, is that he will make a different choice and

your piece will wind up poorly placed.

-

Consider placing pieces on squares where they are

protected by previously placed pieces. Note that since there is no

directionality to the board, pawns may be placed in self-protecting

pairs.

-

Think twice before resigning even after giving up

a substantial material advantage. The peculiarities of a particular

board might allow you to prevent checkmate despite the disadvantage. For

example, experienced chess players automatically resign at the end of a

game where their king is up against a king and a rook. In Go-Chess,

blocked off squares might offer sufficient protection to prevent your

opponent from checkmating you in that end game situation.

![]()